Thursday, Feb 16, 2012

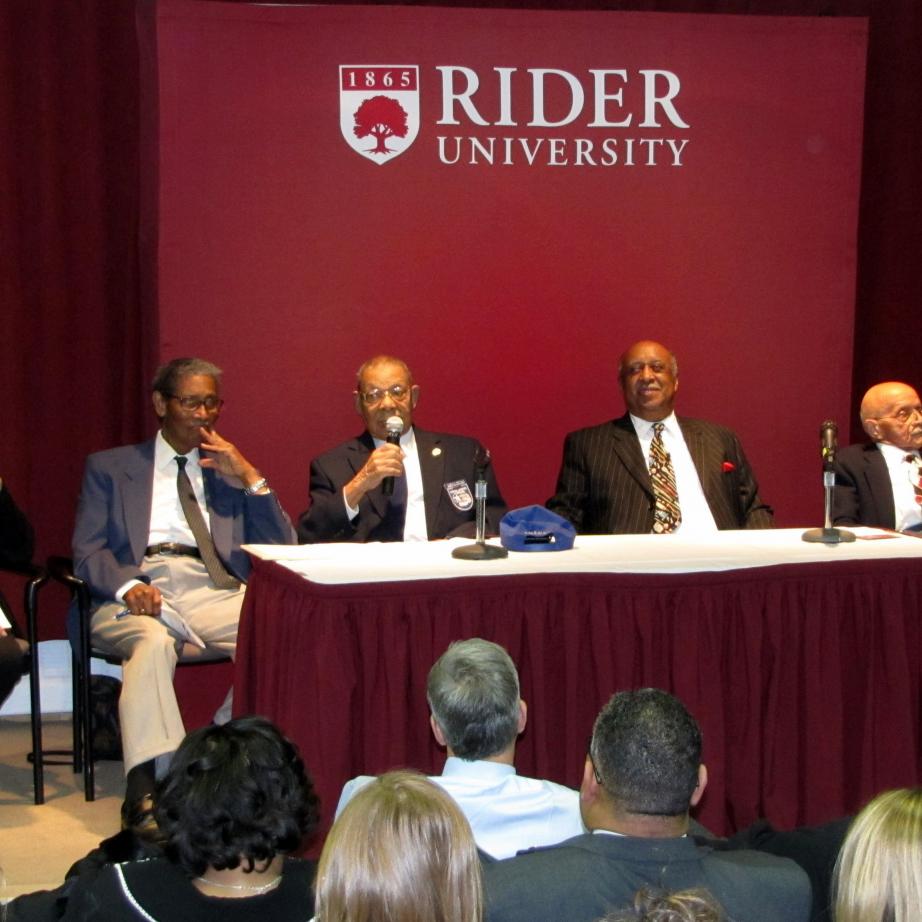

The Rider community had a chance to meet four surviving Tuskegee Airmen during the University’s Black History Month Celebration.

by Meaghan Haugh

As Charles Geter ’55 put it, the 332nd Fighter Group, later known as the Tuskegee Red Tails, was “booked to fail.”

Before 1940, African-Americans were prohibited from flying for the U.S. military. It was not until pressure from Civil Rights activists and journalists resulted in the formation of an all-black squadron based at the Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University) in Alabama during World War II. Similar to the United States at the time, the American military was still racially segregated, and it was not believed that a black man could effectively fly a fighter jet. Yet, more than 1,000 pilots went through the rigorous training at Moton Field and Tuskegee Army Air Field, resulting in one of the most highly respected squadrons of World War II. The new feature film, Red Tails, now out in theaters, depicts the historic story of the first African-American aviators in the U.S. military.

History came to life on February 9, when four surviving Tuskegee Airmen and their family members visited the Lawrenceville campus to share their stories and answer questions during a two-hour event, part of Rider’s Black History Month Celebration.

Geter, the first African-American journalism student at Rider who was later assigned to the U.S. Army’s psychological warfare division in Tokoyo after graduation, introduced the guests, which included surviving Tuskegee Airmen Thomas H. Mayfield; Dr. Leslie A. Hayling, Robert Baker and Rev. Milton Holmes; and Barbara O’Neal, sister of Elwood Thomas, a United States Air Force Major, who died in 1992.

“You are witnessing history this evening. Red Tails gives you a smattering of how these people lived it,” Geter told the standing-room only audience. “It was booked to fail. [Many thought] coloreds could not fight, they did not have the fortitude and if faced with battle, they would run. You had men who were officers in the United States Army who were treated as less than second class citizens.”

Mayfield, who served more than 29 years in the armed forces, said Red Tails gives a good depiction of what he and his fellow airmen accomplished.

“We had to stay together. Red Tails showed we learned how to do something. We did something for the world,” said Mayfield, who acknowledged that the 12,000 people of Tuskegee also included doctors, nurses and mechanics. “You can’t fly the plane without the support of ground people. Support people don’t get recognized. Those people on the ground were the reason we stayed in the air.”

Hayling, a U.S. Army Air Force Aviation Cadet, recalled the many tests and hazing rituals that new cadets at the Tuskegee training fields went through. Tests included reaction tests, light adaptation and color blindness. Meanwhile, new cadets were told to memorize riddles which they would have to recite to the higher ups during roll call. Hayling received a loud round of applause from the audience when he recited several lines by memory.

Baker, a graduate and former track member at Trenton High School, shared how he received a scholarship to the Tuskegee Institute and, later, a letter from Uncle Sam. Though they were serving their country, African-American military men were still discriminated against. Baker, who was a captain in the U.S. Air Force, recalled how once they were told to sit in the back of the bus, but Capt. Benjamin Davis gave them a different order: “Put on your hats and sit where you want to.”

O’Neal, of Hillsborough, N.J., described how her brother was always determined to succeed. He worked three jobs to help finance his education and was the first black man to learn how to fly at Mercer County airport. After being denied admission to the United States Naval Academy because of his race, Driver set his sights on studying at the Tuskegee Institute where he served as a combat pilot, completing 123 combat missions. He later served as the vice chairman of the National Transportation Board.

“He is a hero. He is a legend whose bravery and contributions to his country and his race should never be forgotten,” O’Neal said.