Thursday, Mar 29, 2012

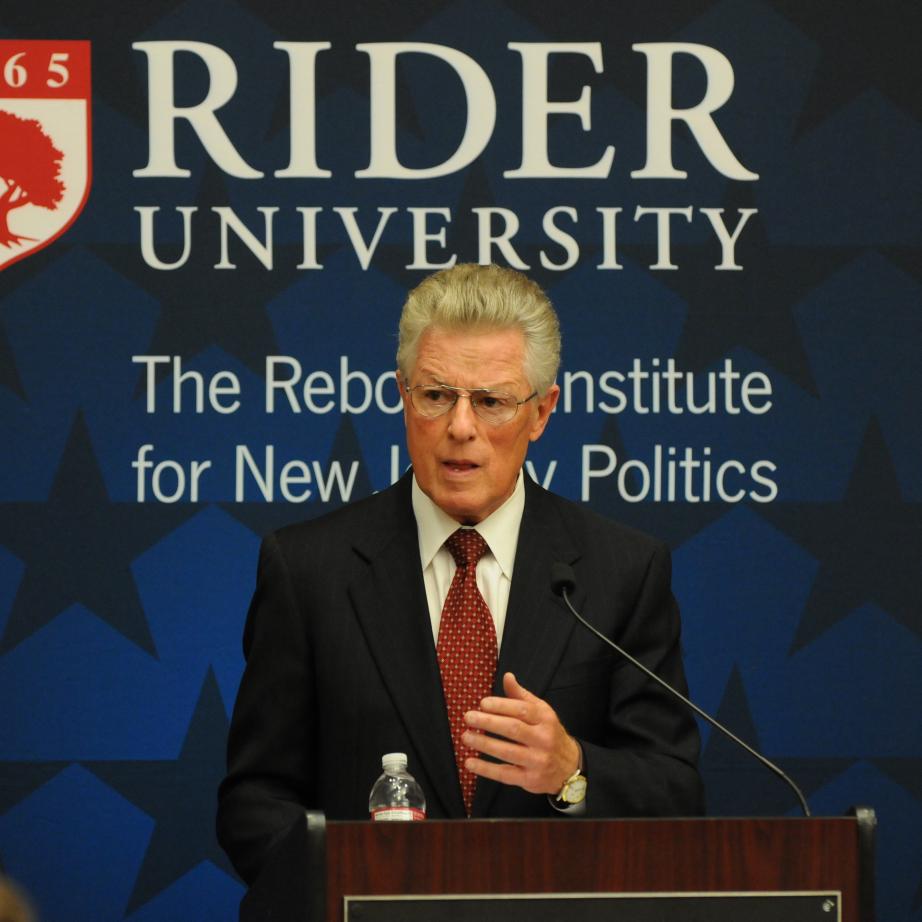

Former New Jersey Gov. James J. Florio spoke at Rider University on March 22 as part of the Rebovich Institute for New Jersey Politics' 'Governing New Jersey Series.' A U.S. Congressman from 1974 through 1990 who also served three terms in the New Jersey General Assembly, Florio was the inaugural recipient of the Rebovich Institute Citizenship Award, presented in June 2011.

by Sean Ramsden

Nearly 20 years after serving as governor of New Jersey, James J. Florio can embrace his status as one of the elder statesmen of the state’s Democratic Party.

“One of the virtues of longevity is that you really get some perspective on things,” Florio told a Mercer Room audience, where he spoke as part of the Rebovich Institute for New Jersey Politics’ Governing New Jersey Series on March 22. A U.S. Congressman from 1974 through 1990 who also served three terms in the New Jersey General Assembly, Florio was the inaugural recipient of the Rebovich Institute Citizenship Award, presented in June 2011.

In his remarks, Florio described the United States as being in a period of dramatic change, the sort not witnessed since the Great Depression in the 1930s. He likened it, historically, to America’s transition from an agrarian to an industrial society in the late 1800s and the post-Civil War Reconstruction Era.

“Those were periods of tremendous stress and alienation, and I’m suggesting that we’re in just such a time now,” said Florio, who now teaches in Rutgers University’s Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy. “We’re not seeing marginal or incremental change, but rather, a fundamental, change that is systemic.”

For all of the fear and disillusionment associated with this tidal wave of change, Florio says it is not necessarily for the worse, though it is incumbent upon politicians and policy-makers to adapt, rather than make repeated, futile attempts to settle changing issues with the same, outmoded thinking.

He invoked the example of the longtime social contract whereby worked exchanged labor for periodic wage increases, promotions, health care benefits and a defined pension system, saying that “we all knows those days are gone.

“It’s troubling and stressful, and the Tea Party Movement is an example of that sort of alienation,” Florio continued. “You hear them shouting, ‘nothing works anymore! I’m working, my wife if working, and we just can’t makes ends meet anymore.’”

However, this frustration, according to Florio, often leads to irrational and misdirected anger rather than constructive debate.

“The less sophisticated among that cohort look for scapegoats. Years ago, it used to be the Jews or the Irish, but now it’s immigrants or Muslims,” he explained. “We have to look deeper, beyond the superficial answers. These rapidly changing events are beyond our ability to cope by doing the same things we’ve always done. We need to change policy to account for the new facts on the ground.”

Among these new facts, Florio mentioned the factors that contributed to the economic meltdown in late 2008.

“We have policies from the 1930s that are incapable of dealing with credit swaps we were seeing,” he explained. “We narrowly escaped some really serious economic consequences – much worse, even, than we have had to endure.”

The ground beneath health care has also shifted faster than policy can keep up with, said Florio, who added that the United States’ employment-based system, framed during World War II, has also become anachronistic.

“The government changed its tax codes to incentivize this system,” he said. “In the auto industry, health care expenses accounted for 12 to 15 percent of the cost of an automobile. No other country in the world builds the cost of health care into the price of the product, but at the time, we had no competition. We do now.”

Florio punctuated the thought by revealing that health care costs now represent 17 percent of the United States’ gross domestic product, the sum of all goods and services produced within a nation’s borders.

“That is simply not sustainable,” he said, adding that American energy policy is similarly outmoded.

Calling for a new policy framework, one more in step with current realities, Florio said the nation must analyze the forces at work, while decision-makers and develop realistic, innovative responses, as opposed to giving politically safe answers.

“We can’t fix the problem if we don’t know what the problem is,” he said. “Change is not bad. “We just have to frame our responses to deal with the consequences.”

For instance, he pointed to employment, saying the job market needs to be dealt with in ways the nation is not accustomed to.

“The stock market is doing very well; productivity is good. Companies have so much cash on hand that corporate treasuries are almost embarrassing,” Florio explained. “And yet, we’re still concerned about employment, or rather, unemployment. We have to ask, ‘is this a new era of prosperity?’ The auto industry has come back, but there are a whole lot of auto workers out of work. Is this going to be the new norm, where 8 to 10 percent of people being out of work is considered full employment?”

For statistical purposes, traditional full employment is considered to be between 5 and 6 percent, Florio said.

“This, obviously, is a message the politicians won’t like to deliver,” he continued. “But the point is that there are truths that must be addressed rather than deluding ourselves. That may be satisfying for a while, but it always catches up.”

Still, Florio once again drew on his well-earned perspective, expressing hope for the future through the words of a leader from the past, Winston Churchill: “Americans always seem to get it right after they’ve exhausted all the alternatives,” he said, echoing the former British prime minister.